The Present: PubMed is going for the mass.

The Present: PubMed is going for the mass.

This is a continuation of Part I (click here to read)

… Well, it seems that some of these enhancements are in the process of being implemented, considering recent major changes to PubMed’s interface:

1. Automatic Term Mapping (ATM).

ATM is the most recent, most radical and yet most poorly announced change.

Suddenly, when preparing a Master Class, searching via the search bar gave different, sometimes odd results. PubMed looked the same, but the DETAILS-tab showed the automatic search mapping (ATM) to be different. PubMed’s “New and Noteworthy” confirmed that ATM had been drastically modified. See here for the announcement’.

Consider this (given) example. Searching gene therapy would give:

with the Old ATM:

“gene therapy”[MeSH Terms] OR gene therapy[Text Word]

and the NEW ATM:

“gene therapy”[MeSH Terms] OR (“gene”[All Fields] AND “therapy”[All Fields]) OR “gene therapy”[All Fields].

Thus the new ATM expands the search:

1. by searching in All Fields instead of the tw-field (Title, Abstract, MeSH)

2. by splitting multi-word terms. Gene therapy is no longer sought as “gene therapy”, but as “gene” and “therapy”.

According to the NLM this facilitates finding synonyms like “gene silencing therapy…” and finding X in the author field. They should add: whether you WANT TO FIND IT OR NOT. Thus from now on you will search all fields automatically, including author, journal and address field.

Should I be glad to find more? NO, I use the Single Citation Mapper if I want to find a citation by author X, and I rather expand the search by adding terms that matter.

Suppose I would like to search´gene silencing therapy´ as well, then I would add gene silencing therap*[tiab], since searching for these words in a string will broaden the search without increasing noise.

However gene silencing (preventing a gene to work, i.e. by antisense oligo’s OR siRNA) is not really a gene therapy (insertion of a gene). So for most searches on ´gene therapy´ ´gene silencing´ is no valuable addition. And if it would be, MeSH like “Gene Silencing” and its narrow term RNA Interference should be included as well.

With gene therapy ATM will now (June 5th) retrieve 90942 hits instead of 36557, thus a surplus of 54385 hits, that is 2 ½ times as much!!! The expansion does add very little meaningful terms. It mainly retrieves citations with therapy in ANY field and:

- gene as an author [au] : 53 extra hits

- gene in the addressfield [ad], like hkj@gene.com or Department of Gene Regulation : 1327 extra hits

- gene in the journal name, including “Gene” : 1487 extra hits

- gene and therapy in the abstract/MeSH without direct connection to each other: papers about the impact of gene expression profiling on breast cancer outcomes (following chemotherapy NOT gene therapy), of experimental studies on change in gene-regulation following therapy etcetera: the majority of the extra hits. Estimation > 90%?: does anyone realize how often ‘gene’ and ‘therapy’ (in text, MeSH, subheadings and all other fields?) are used outside the context of gene therapy?

I guess I’m not the only one that is not pleased with this “enhancement”. Most users I know use Pubmed for subject searching and they unanimously experience the high number needed to read (high recall, low precision) as the major obstacle. ATM will only make this worse.

And what about:

- people unaware of any changes and just relying on the search bar for subject searching, supposing it works the same as before?

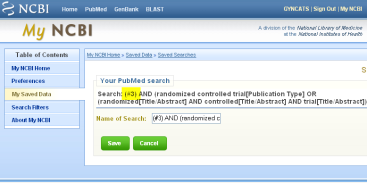

- the effect on alerts (RSS or MyNCBI)?

- important updates of prior searches, i.e. for systematic reviews. With ATM you may retrieve MUCH more irrelevant papers. How to explain different results over time?

- Although of minor importance, our courses, tutorials, exercises, the PubMed book my colleagues just wrote, all have to be adapted.

Thus I stop advising students/meds to simply use the search bar and just check the details, because this will surely frustate them. Rather I will advise them to add tags themselves: Look for the appropriate MeSH for Y in the MeSH-database and add Y*[tiab] as well. Even for simple subject searches!

Who wants the search d-dimer diagnosis lung embolism to be translated as:

(“fibrin fragment D”[Substance Name] OR (“fibrin”[All Fields] AND “fragment”[All Fields] AND “D”[All Fields]) OR “fibrin fragment D”[All Fields] OR (“d”[All Fields] AND “dimer”[All Fields]) OR “d dimer”[All Fields]) AND (“diagnosis”[Subheading] OR “diagnosis”[All Fields] OR “diagnosis”[MeSH Terms]) AND (“lung”[MeSH Terms] OR “lung”[All Fields]) AND (“embolism”[MeSH Terms] OR “embolism”[All Fields])

Very impressive, isn’t it, but the correct MeSH for lung embolism, pulmonary embolism is not mapped!!!!

Is it good then for preclinical guys, i.e.molecular biologist? Suppose you’re looking for signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (that’s one protein), most lab people will use either the whole word or stat 3, stat(3), stat-3 or stat3

1. stat 3 maps to: (“Stat”[Journal] OR “stat”[All Fields]) AND 3[All Fields] = 4031 hits

2. Stat-3 maps to: stat-3[All Fields] = 591 hits

3. stat3 maps to: “stat3 transcription factor”[MeSH Terms] OR (“stat3″[All Fields] AND “transcription”[All Fields] AND “factor”[All Fields]) OR “stat3 transcription factor”[All Fields] OR “stat3″[All Fields] = 4639 hits

(Note that grey terms are superfluous: by searching stat3 you already find stat3 transcription factors)

Not very consistent and only the 3rd variation will be mapped to the proper MeSH, BUT (like 1.) will also give things like:

- DeltaB=(1.18+/-0.09_{stat}+/-0.07_{syst}+/-0.01_{th

eor})x10;{-3}

eor})x10;{-3}

- EPI STAT, version 3.2.2.

- Via Santa Marta n. 3 (address) and pH-stat

- D Stat (author) and vol nr 3.

Thus it would be better to search for either merely

“stat3 transcription factor”[MeSH Terms]

or add synonyms (with OR) like stat-3[tiab], stat3[tiab], “stat 3″[tiab], “signal transducer and activator of transcription 3″[tiab].

This will increase precision and even recall.

However, one has to know how to find the correct terms and tags.

2. Citation Sensor

The renewed ATM was introduced together with the Citation Sensor that recognizes combinations of search terms characteristic of citation searching, e.g. volume nrs, author names, journal titles and publication dates, which it then matches to citations. These are shown separately in a yellow area above the retrieval.

Searching for limpens oncogene indeed suggests one paper of Limpens in Oncogene. This option can be very handy when one wants to retrieve a citation.

However typing: gene therapy 2007 405 gives 59 hits, but the citation sensor does not sense the specific paper in “Gene” year 2007, vol 405 (although retreived).

The Single Citation Mapper would have done better…. giving a single (correct) hit on both occasions.

Donna Berryman came to a very similar conclusion when writing to the MedLibList. She shows some other nice examples (i.e. that the citation sensor shows 4 citations from the journal Cancer by author Lung when searching lung cancer!!).

Donna explains that at the NLM booth at MLA, she was told that Pubmed changes were made to meet the wishes of a “significant” number of people that were going to PubMed, entering an author name and a journal title (with no field qualifiers) and expecting to retrieve a particular citation.

I’ve seen the nih.gov webmeeting presentation Donna referred to (click here)] as well as another (click here) (tips of the MedLib twitters @pfanderson and @eagledawg. Eagledawg (Nikki) also wrote 2 blogposts about this subject, see here (May) and here (June) )

It was quite revealing to see that empasis was given to numbers: number of visitors, numbers of queries versus number of documents and speed:

“if the query takes 2-3 minutes we loose users!”.

Well I can understand that NLM doesn’t want to discourage potential users, but I don’t understand why all functionalities have to be mixed in a way that it only serves the quick and dirty searches and even not very effectively. As Donna puts it: the new ATM is moving PubMed away from being a subject-based search. Again, most of my customers do subject searching.

3. Advanced search beta

Advanced search is a beta (version) and thus may be adapted based on findings and feedback (see here for announcement)

I don’t really know what to think of it. Firstly I wonder whether the Advanced Search is an extra option or meant to replace the present front page in due course. Secondly the Advanced Search looks quite complex, but not particularly advanced. The regular front page has more options (although hidden). This is certainly not an advanced tool for librarians, but is it an adequate tool for other users, clinicians or researchers?

Advanced Search beta consist of 5 separate “boxes”.

- The search-bar with a preview or a search option. Surprisingly the search option brings you back to the old front page. When you opt for “preview” you stay in the ‘advanced’ search.

- Search History showing the last 5 searches. If you exceed 5 searches a “More History” button appears. When clicked it brings up the full display.

- Seach by selected Fields. There are 3 default lines set up for Author, Journal and Publication date searching. Thus again, emphasis is given to reference instead of subject searching. Similar to the Single Citation Mapper, there is an auto-complete feature for authors and journals. On the right of each line is an index-feature.

If you want to do a subject search (which in fact most advanced searchers do), you have to open the list of fields using the pull-down menu. However, for MeSH terms this is not ideal. Suppose you want to look up the MeSH for recurrent pregnancy loss (the term mostly used by clinicians). The MeSH is Abortion, Habitual. You won’t find the MeSH by looking at recur….. In effect, you won’t find it by looking up habit…. either. You have to start typing abortion…!?

If you want to do a subject search (which in fact most advanced searchers do), you have to open the list of fields using the pull-down menu. However, for MeSH terms this is not ideal. Suppose you want to look up the MeSH for recurrent pregnancy loss (the term mostly used by clinicians). The MeSH is Abortion, Habitual. You won’t find the MeSH by looking at recur….. In effect, you won’t find it by looking up habit…. either. You have to start typing abortion…!?

When you find an appropriate MeSH, you can choose to search for the MeSH coupled to a particular subheading (i.e. haemonchiasis/blood). You can see immediately how many hits will be retrieved (63).

Suppose a clinician wants to know whether PGS is indicated in RPL. He pulls open the MeSH-field, types recurrent pregnancy loss, adds another MeSH-field and fills in preimplantation genetic screening, because he thinks PubMed will match it for him.

He clicks a few limits because he thinks that might help to narrow his search, clicks the search button, waits and … ends up the regular front page showing zero results. So all steps he took didn’t lead him anywhere, because the appropriate MeSH (Abortion, Habitual and Preimplantation Diagnosis) weren’t found and he still has no clue as to what terms he should use.

Even if the correct MeSH is found, the notation may be quite misleading. For example, after typing lung cancer into the box next to ‘Search MeSH terms’ , the History in PubMed will show lung cancer[MeSH Terms], whereas “lung cancer” is NOT the MeSH term. Thus people are going to think that lung cancer is the MeSH, because it looks like this. If they look in the Details box, however, they’ll see the real “lung neoplasms”[MeSH terms]. How are people going to know what’s what? (Thanks to Donna for providing this example).

At least, in case of lung cancer, the correct MeSH-term is being searched. In contrast, a term like Lung embolism is not searched as Pulmonary embolism[mesh], and gives zero hits. Funny, because searching via the normal search bar would at least translate lung embolism in embolism[mesh] and lung[mesh]. (and there are several tricks whereby you can subsequently find the proper MeSH)

Thus, in Advanced Search Beta, searching MeSH via ‘search MeSH-terms’ will only work when you know the (exact) MeSH-term in advance.

- The 4th box is really the limits-tab from the usual front page, but shown in full. A nice option is that you can lock certain limits while unlocking others (that is you can apply one limit to the next search and other limits to this and subsequent searches).

- The 5th box is (again) an Index of Fields. However it allows you to enter multiple terms.

In short, I’m not particularly impressed by this advanced search beta. It is too complex for a quick and dirty search as well as for a reference search. However, it is also not very well suited for an (advanced) subject search. It is not possible to look up any MeSH other than by index, and even this often goes wrong.

Some important functionalities are not included, like the clinical queries. Furthermore by displaying limits so prominently, many people will automatically use them. Personally I’m very reticent in using limits, because you miss non-indexed (i.e. recent) papers.

So I agree with tunaiskewl

“I stumbled across a beta Advanced Search in PubMed today. Has anyone else played with this? It appears that it merges the Preview/Index, History, Limits, and field searching screens all together in one place. Perhaps this will make some of PubMed’s features more obvious to searchers, but I’m not seeing too much benefit to it otherwise…”

4. Other minor recent changes include:

- Create Collection in MyNCBI by one step via the send to option (this is wonderful!)

- PubMedID (ID for Pubmed Central, at the bottom right)

- Collaborators -display (separate from autors)

- In Abstract Plus – (very popular with users, dynamic display format)

- Blue side bar gone in certain display formats. Again this is done to make room for new functionalities (bad!, takes me 2 steps to go back to MeSH, Clinical Queries or whatsoever)

—————–

The Present: PubMed is going for the mass.

Dit is een vervolg op deel 1(zie hier)

Het lijkt erop dat enkele aanpassingen inmiddels doorgevoerd zijn, t.w.

1. Automatic Term Mapping (ATM).

Hoewel ATM een zeer ingrijpende verandering is, is de gebruiker hier nauwelijks van op de hoogte gesteld.

Ik kwam er bij toeval achter toen ik met een collega een keuzevak voor 2e jaars voorbereidde. Zoeken via de zoekbalk gaf heel andere resultaten, terwijl er uiterlijk aan PubMed niets te zien viel. De Details tab toonde een geheel afwijkende automatic term mapping, ook wel ATM of mapping genoemd. In PubMed’s “New and Noteworthy” werd dit wel aangekondigd, maar hoe velen lezen dit?

Men geeft hier het volgende voorbeeld:

Gene therapy wordt als volgt gemapt:

met de oude ATM: “gene therapy”[MeSH Terms] OR gene therapy[Text Word]

met de nieuwe ATM: “gene therapy”[MeSH Terms] OR (“gene”[All Fields] AND “therapy”[All Fields]) OR “gene therapy”[All Fields].

Dus de nieuwe ATM breidt de search uit:

1. door op All Fields te zoeken ipv. het tw-field (Titel, Abstract, MeSH)

2. door termen bestaande uit meerdere woorden op te hakken in de individuele woorden. Gene therapy wordt niet langer gezocht als “gene therapy”, maar als “gene” en “therapy”.

Volgens de NLM zoek je daarmee ook op synoniemen als “gene silencing therapy…” en vind je ook X in het auteursveld als je op X zoekt. Eigenlijk hadden ze moeten zeggen; ongeacht of je het wilt vinden. Dus van nu af aan zoek je automatisch in alle velden als je zelf geen tags toevoegt.

Of ik blij ben dat ik nu meer vind? Nou nee, ik gebruik de Single Citation Mapper wel als ik een citatie Y door auteur X wil vinden en ik breid searches liever uit door er relevante termen aan toe te voegen.

Dus hooguit zou ik gene silencing therap*[tiab] aan de search toevoegen, als ik heel breed wil zoeken. Dit breidt mijn search uit zonder onnodige ruis. Echter, goed beschouwd, is “gene therapy” (gentherapie, invoegen van een gen) toch wezenlijk anders dan gene-silencing (voorkomen dat een gen werkt door antisense oligo’s of siRNA). Daarom lijkt het me dit begrip voor de meeste searches over gentherapie niet echt bruikbaar. (Tussen 2 haakjes: er is een goede MeSH voor “Gene Silencing”, de nauwere term is RNA Interference)

Met gene therapy vindt ATM nu (5 juni) 90942 hits i.p.v. 36557, dus 54385 extra hits, dit is 2 ½ keer zoveel!!! De meeste van deze extra hits zijn niet relevant. Je vind nl ook citaties met therapy in ELK veld en:

- gene als auteur : 53 extra hits

- gene in het adresveld: hkj@gene.com of Department of Gene Regulation : 1327 extra hits

- gene in de tijdschrifttitel, zoals “Gene” : 1487 extra hits

- gene en therapy in het abstract/de MeSH zonder enig betekenisvolle relatie: artikelen over het effect van gene expression profiling op de prognose van borstkanker (na chemo, niet na gentherapie), studies over veranderingen in genregulatie na therapie X. De meerderheid van de extra hits zal onder deze noemer vallen.

Waarschijnlijk vinden meer mensen ‘deze enhancement’ niet prettig. De meeste gebruikers die ik ken zoeken op onderwerp en het grootste probleem dat ze hierbij ondervinden is dat ze teveel vinden wat niet relevant is (hoog number needed to read). ATM verergert dit alleen maar.

En wat te zeggen van:

- mensen die zich van niets bewust zijn en de zoekbalk net zo gebruiken als vanouds

- effect op bestaande alerts (RSS of MyNCBI)?

- updates van eerdere searches, bijvoorbeeld voor een systematisch review. Ten gevolge van ATM vind je dan opeens na een bepaald tijdstip meer hits met dezelfde search (indien geen tags gebruikt)

- het aanpassen van cursussen, tutorials, opdrachten, het PubMed boek dat mijn collega’s net hebben gemaakt? En wie zegt dat dit het einde is?

Van nu af aan zal ik (bijna) iedereen adviseren om niet langer maar via de zoekbalk te zoeken en slechts de Details te controleren, maar om de meest geschikte Mesh-term(en) te gebruiken en evt. op een of meer synoniemen in titel en abstract te zoeken.

D-dimer diagnosis lung embolism wordt volgens de huidige ATM vertaald als:

(“fibrin fragment D”[Substance Name] OR (“fibrin”[All Fields] AND “fragment”[All Fields] AND “D”[All Fields]) OR “fibrin fragment D”[All Fields] OR (“d”[All Fields] AND “dimer”[All Fields]) OR “d dimer”[All Fields]) AND (“diagnosis”[Subheading] OR “diagnosis”[All Fields] OR “diagnosis”[MeSH Terms]) AND (“lung”[MeSH Terms] OR “lung”[All Fields]) AND (“embolism”[MeSH Terms] OR “embolism”[All Fields])

Indrukwekkend niet, maar de meest geeigende MeSH, pulmonary embolism wordt niet gevonden!!!!

Is het dan goed voor de moleculair biologen e.a. preclinici? Stel dat je bijv. op zoek bent naar het eiwit signal transducer and activator of transcription 3. De meesten zoeken dan op het hele woord of stat 3, stat(3), stat-3 or stat3

1. stat 3 geeft: (“Stat”[Journal] OR “stat”[All Fields]) AND 3[All Fields] = 4031 hits

2. Stat-3 geeft: stat-3[All Fields] = 591 hits

3. stat3 geeft: “stat3 transcription factor”[MeSH Terms] OR (“stat3″[All Fields] AND “transcription”[All Fields] AND “factor”[All Fields]) OR “stat3 transcription factor”[All Fields] OR “stat3″[All Fields] = 4639 hits

(De grijze termen zijn dus eigenlijk overbodig want door op stat3 te zoeken vind je die al.

Niet erg consistent vertaald; alleen variatie 3 wordt gemapt met een MeSH, MAAR vindt evenals 1 geheel irrelevante hits als:

- DeltaB=(1.18+/-0.09_{stat}+/-0.07_{syst}+/-0.01_{th

eor})x10;{-3}

eor})x10;{-3}

- EPI STAT, version 3.2.2.

- Via Santa Marta n. 3 (address) and pH-stat

- D Stat (author) and vol nr 3.

Daarom is het beter om of alleen op de MeSH te zoeken

“stat3 transcription factor”[MeSH Terms]

of om daar synoniemen aan toe te voegen als stat-3[tiab], stat3[tiab], “stat 3″[tiab], “signal transducer and activator of transcription 3″[tiab].

Hierdoor neemt de precisie en zelfs de recall toe. Maar je moet wel weten hoe de termen en tags te vinden.

2. Citation Sensor

Tegelijk met de nieuwe ATM werd ook de Citation Sensor ingevoerd. Deze herkent termen die karakteristiek zijn voor citaties. Als Citaties gevonden worden, worden ze apart in een geel vlak boven de zoekresultaten getoond.

Wanneer je op limpens oncogene zoekt zijn wordt het artikel van Limpens in Oncogene getoond. Deze optie kan handig zijn als je een citatie wil vinden.

Zoek je echter: gene therapy 2007 405 dan pikt de citation sensor niet het artikel in “Gene” 2007, vol 405 op temidden van de 57 hits.

De Single Citation Mapper zou dit beter gedaan hebben: 1 enkele goede hit in beide voorbeelden.

Donna Berryman kwam tot dezelfde conclusie in haar MedLibList-Mail. Ze geeft nog een paar andere leuke voorbeelden, zoals dat de citation sensor 4 citaties vindt van auteur Lung in het tijdschrift Cancer als je op lung cancer zoekt!!).

Donna vertelt dat ze op een NLM stand op de MLA hoorde dat er PubMed veranderingen doorgevoerd werden ten behoeve van een niet te verwaarlozen groot aantal mensen die alleen naar PubMed kwamen om een auteur of tijdschrifttitel in te voeren, omdat ze zo dachten een bepaald artikel te kunnen vinden

Hier is (waarschijnlijk) de webmeeting waar Donna aan refereert en hier een andere (tip van de MedLib twitters @pfanderson en @eagledawg. Eagledawg (Nikki) schreef, zo las ik later, ook 2 blogberichten over dit onderwerp, zie hier (Mei) en hier (Juni) )

Ik vond het nogal onthutsend dat getallen zo zwaar telden.

“if the query takes 2-3 minutes we loose users!”.

Ik begrijp natuurlijk wel dat de NLM ook degenen wil tegemoetkomen die alleen maar een artikeltje zoeken, maar moet dat ten koste gaan van andere functionaliteiten? Zelfs zoeken op een specifiek artikel verloopt niet altijd vlekkeloos. Het lijkt erop dat, zoals Donna het zegt, met de nieuwe ATM het zoeken op onderwerp minder belangrijk wordt. Nogmaals, de meeste mensen die ik ken zoeken op onderwerp.

3. Advanced search beta

Advanced search is een beta (versie), dus nog in de probeerfase. (zie hier).

Ik weet nog niet helemaal wat ik ervan moet denken. Komt het naast of in plaats van de oude entree? Ik het er nogal erg complex uitzien en toch niet erg geavanceerd. Niet alle opties van de normale openingspagina zijn aanwezig.

Er zijn 5 verschillende vakjes.

- De zoekbalk met een preview en een zoekoptie. Gek genoeg kom je als je op search klikt weer op de oude vertrouwde Pubmed pagina terecht. Als je daarentegen voor “preview” kiest blijf je wel in de ‘advanced’ search.

- Search History. Bij meer dan 5 searches moet je op “More History” klikken om de volledige zoekgeschiedenis te kunnen zien.

- Seach by selected Fields. Standaard kun je op Author, Journal and Publication date zoeken. Dus wederom erg gericht op het vinden van referenties. Handig is de auto-complete-functie voor auteurs en tijdschriften (net als in de Single Citation Mapper). Rechts is een aanklikbare index.

Je kunt in andere velden zoeken door op het pull-down menu te klikken. Het is echter niet erg handig om zo op MeSH te zoeken. Stel dat je op recurrent pregnancy loss wil zoeken. De MeSH is Abortion, Habitual. Dat vindt je dus niet door op recur….. te zoeken in de index, en ook niet door op habit…. te zoeken.(in een update van de engelse versie heb ik een aantal voorbeelden toegevoegd die laten zien dat het zoeken van MeSH-termen via Advanced Serach beta niet goed verloopt, t.z.t zal ik die hier vertalen)

Je kunt in andere velden zoeken door op het pull-down menu te klikken. Het is echter niet erg handig om zo op MeSH te zoeken. Stel dat je op recurrent pregnancy loss wil zoeken. De MeSH is Abortion, Habitual. Dat vindt je dus niet door op recur….. te zoeken in de index, en ook niet door op habit…. te zoeken.(in een update van de engelse versie heb ik een aantal voorbeelden toegevoegd die laten zien dat het zoeken van MeSH-termen via Advanced Serach beta niet goed verloopt, t.z.t zal ik die hier vertalen)

Je kunt als je een MeSH vindt, deze alleen zoeken of met een subheading eraan gekopeld (bijv. haemonchiasis/blood). Het aantal hits (63) is direct te zien.

- Het 4e vak is eigenlijk de limit-tab, maar dan volledig getoond. Nieuw is dat je bepaalde limieten aan kan laten staan (locked), terwijl je andere alleen voor de volgende search gebruikt.

- Het 5e vak is weer een index van alle velden. je kunt hier wel verschillende termen tegelijk invoeren.

Samenvattend, ik ben niet bijzonder onder de indruk van deze ‘geavanceerde’ seach optie. het is te ingewikkeld en te weinig intuitief voor een snelle search of het opzoekwerk, maar het is ook niet erg geschikt voor een geavanceerde search. Met name omdat je de MeSH alleen via indexen kunt opzoeken. Ook zijn er minder opties. De Clinical Queries ontbreken bijvoorbeeld. Aan de andere kant zijn de Limits zo prominent aanwezig dat gebruikers misschien sneller dan normaal geneigd zijn ze toe te passen. Persoonlijk gebruik ik ze zeer beperkt!

4. Kleinere veranderingen

- Je kunt een Collection in MyNCBI nu simpel aanmaken via de send to option (perfect!)

- PubMedID (ID voor Pubmed Central, rechtsonderaan)

- Collaborators -display (gescheiden van auteurs)

- In Abstract Plus

- De linker blauwe balk (met geavanceerde opties) wordt in bepaalde display formats niet meer getoond. Hierdoor zou er meer ruimte komen voor nieuwe functionaliteiten (als de related reviews), maar ik vind het heel vervelend omdat ik meer stappen nodig heb om na elke individuele zoekactie weer naar de MeSH of Clinical Queries terug te gaan.

![]() Paul Glasziou, GP and professor in Evidence Based Medicine, co-authored a new article in the BMJ [1]. Similar to another paper [2] I discussed before [3] this paper deals with the difficulty for clinicians of staying up-to-date with the literature. But where the previous paper [2,3] highlighted the mere increase in number of research articles over time, the current paper looks at the scatter of randomized clinical trials (RCTs) and systematic reviews (SR’s) accross different journals cited in one year (2009) in PubMed.

Paul Glasziou, GP and professor in Evidence Based Medicine, co-authored a new article in the BMJ [1]. Similar to another paper [2] I discussed before [3] this paper deals with the difficulty for clinicians of staying up-to-date with the literature. But where the previous paper [2,3] highlighted the mere increase in number of research articles over time, the current paper looks at the scatter of randomized clinical trials (RCTs) and systematic reviews (SR’s) accross different journals cited in one year (2009) in PubMed.

In a previous post

In a previous post

Recent Comments